A long-awaited increase in energy-efficiency requirements for new homes is part of revised Australian construction standards that have taken effect this week.

All new homes must achieve a minimum 7-star whole-of-home energy rating from October, following a six-month transition period.

It’s a crucial step in responding to the climate crisis and decarbonising Australian society. It will also make our homes more affordable and comfortable to live in, and improve our health and wellbeing.

These regulations affect the roughly 150,000 new homes built each year across Australia. But what about the other 10.8 million homes we’re already living in?

Any transition towards a low-carbon future must include big improvements to existing housing. Housing accounts for around 24% of overall electricity use and 12% of carbon emissions in Australia.

As a nation we spend at least as much on renovations and retrofits as on building new housing. Upgrading the energy performance of existing homes should get at least as much attention as new homes to help make the transition to low-carbon living.

How do you know if a home’s a lemon?

Australians can access lots of information about the performance of appliances and vehicles, but almost nothing about the quality and performance of our housing.

When buying an appliance or a car we can see how much energy it will use and how much it will cost to run. We can then compare options and improve our decision-making.

We also have rights if our purchase doesn’t perform as described. Australia doesn’t have a specific “lemon law” like the United States. Nonetheless, a raft of laws protect buyers of both new and used vehicles.

Yet when it comes to our biggest and most important buying decision – buying or renting a home – we have a right to precisely nothing in terms of information on its energy efficiency and readiness for a sustainable future. What little information is provided is often misleading.

Energy performance must be disclosed in other countries

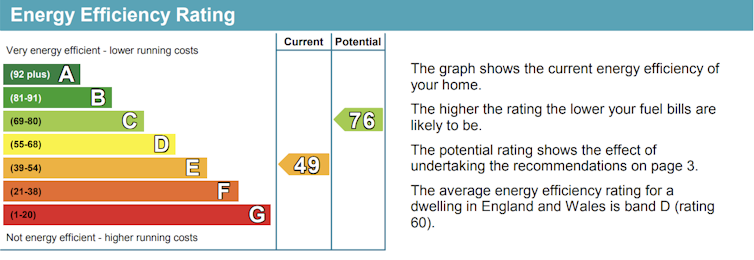

Housing energy rating schemes are used worldwide. These schemes rate and compare the energy use of housing to help people decide what they will rent and buy.

Energy ratings are important. They tell us how much we are likely to spend on essential activities such as heating and cooling our homes. Amid a cost-of-living crisis, including soaring energy prices, this matters to all Australians, particularly those doing it tough.

Australia had a world-leading housing energy rating scheme when it was adopted in the ACT in 2003. Since then progress has stalled on a national scheme similar to those established globally in recent decades.

Energy ratings also reveal the underlying condition of our housing. Housing in Australia built before the early 2000s typically has only a 1-3 star energy rating. That level of performance more than doubles its energy bills and emissions compared to a new home.

People looking to buy or rent could avoid the housing equivalent of a lemon if we had a national scheme that requires a standard, independently verified energy performance assessment be made available to them. This would create an incentive for sellers and landlords to improve the energy performance of housing. It would also give policymakers a national picture of where retrofit schemes could best be targeted to meet our emission-reduction commitments.

What are the prospects for such a scheme?

Discussions are taking place in Australia about introducing a requirement for households to obtain some sort of energy or sustainability rating on their dwelling, potentially at point of sale or lease. A similar requirement is in place in other locations like Europe, the United Kingdom and even the ACT.

We have the resources and knowledge to establish a robust system that is: accurate and holistic, robust and consistent, applied and clear, transparent and adaptive.

The benefits of such a scheme include:

- encouraging energy-efficient retrofits of existing homes for the health and comfort of Australians

- supporting social equity between people living in older homes and those in newer homes, and particularly for renters and low-income households

- giving Australians a better understanding of the houses they rent or buy, in the same way they choose their appliances

- reducing emissions from housing to help achieve the target of net-zero emissions

- providing information to inform and develop policies for existing homes that then align with policies for new homes.

The key is not to do a cheap job on this. That would waste the effort, time and money we put into retrofitting homes, and risk us missing our climate commitments. It would also mean our most vulnerable households would find it even more difficult to access decent, energy-efficient housing.

Doing a proper job means we will all have access to independent verified information. It will help fix market failures and provide peace of mind about the places we live, with the potential to upgrade them reliably and cost-effectively.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.